2013/11/02 21:29 UTC

Cosmos with Cosmos is a weekly series that encourages people to

get together and watch Cosmos with a cosmo(politan) or drink of your

choice. We're posting weekly episode recaps and discussion through

February of 2014. This series is made possible by members of the

Planetary Society. If you like what you're reading, please consider joining the Society or donating $10 to help support projects like this in the future. To learn more about this series and find out how to watch Cosmos, see our introduction.

This special post is from Adolf Schaller, the creator of the painting shown below which was featured heavily in Cosmos, Episode 2, "One Voice in the Cosmic Fugue." He was kind enough to share the intense experience of creating this painting for the series back in the late 1970s.

-Casey Dreier

Adolf Schaller

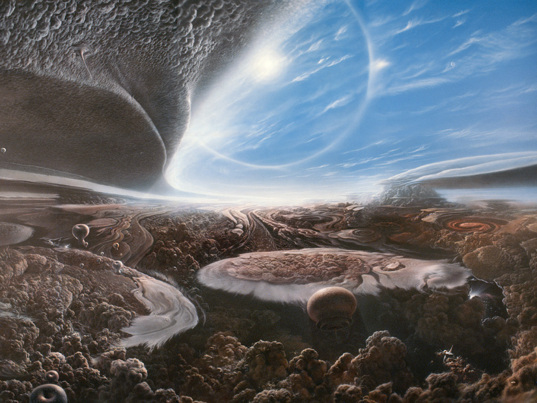

Hunters, Floaters, and Sinkers

This painting speculates about possible forms of life on a Jupiter-like

gas giant. Airbrushed water-based acrylic. 90 x 120 in (7.5 x 10 ft).

Dimensions: 90 x 120 inches (7.5 x 10 feet)

Medium: Airbrushed water-based acrylic.

Construction: The HFS mural consisted of nine 30 x

40-inch illustration board panels mounted on a plywood backing. The 30 x

40-inch boards were individually worked as separate panels before

mounting using a high-quality rubber cement the day before the scheduled

shooting. This operation included the application of a special tape and

finishing touches to conceal the seams between the panels for the

sequence shooting and photography for the book.

Image scale: 1 degree of arc : 1 inch. Its angular

dimensions were thus a very wide-angle 90 x 120 degree view. The choice

vantage point for a viewer appreciating the entire scene was directly

over the center panel some 60 inches from the surface at that point.

However, no attempt was made to introduce the distortion which would

accrue from mapping a wide-angle area onto a flat surface. This was done

in order to permit the camera to zoom in and pan, 'truck' or travel

across any region of the painting without encountering any local

distortions.

In September of 1978 I received a phone call from Jon Lomberg and

Carl Sagan asking me if I would be interested in working on their

upcoming PBS science series, "Cosmos". Without hesitation I said yes.

They asked me about working on several subjects, but one in particular

held a special significance for Carl, and he was keen to see the concept

treated with as much realism and scientific accuracy as possible, as

well as investing it with an aesthetic that evoked a sense of wonder. He

wanted it to excite the imagination, to plausibly suggest what might be

within the realm of natural possibility. I shared his enthusiasm for

the topic; fortunately, I had good long head start on what would become

an unexpectedly daunting and difficult challenge.

It just so happened that I had been producing a series of

increasingly large paintings depicting the atmospheric environments of

Jovian-class or gas-giant planets - panoramic cloudscapes - for quite a

number of years previously, with the intention of eventually creating a

series based on hypothetical organisms and even whole ecosystems which

could conceivably evolve in such habitats. These early studies included

illustrations which appeared in Astronomy magazine and educational slide

sets produced by Encyclopedia Britannica (from 1974-1976), Starlog and

Future-Life magazines (in particular, a scene depicting a balloon probe

afloat above the cloudtops of Jupiter's Great Red Spot (1977), and a 30 x

40-inch Jupiter cloudscape depicting another balloon probe I had

donated to the Flandrau Planetarium in Tucson in 1977-1978.

My principle sources of inspiration came seven years earlier. On one

of my regular weekend visits to my favorite library back in 1971, I came

across a new arrival in the science section: a copy of the book, "

Intelligent Life in the Universe",

by Iosif Shklovskii as expanded by Carl Sagan, published in 1968. I was

15 at the time, and that book completely absorbed me. Their description

of a biosphere entirely suspended within and supported by an

atmospheric environment was my first exposure to the concept. By the

time I came across Arthur C. Clarke's 1972 short story, "A Meeting with

Medusa" not long after my reading of Carl's Cosmic Connection in late

1973, I was enchanted by the concept. A burgeoning ecosystem of diverse

creatures inhabiting the clouds of gas-giant planets became a

preoccupation, stimulating my imagination in many detailed conceptual

drawings and cloudscape studies.

I had by then already developed a serious interest in astronomy and

physics with the goal of obtaining a degree, but reading this book (not

long after studying Darwin's "On the Origin of Species", and Sagan's

"The Cosmic Connection" later on in 1973) had a powerful influence on my

thinking. It gathered my varied astrophysical interests and welded them

together within the context of life: the nucleosynthesis of heavy

elements, biogenic conditions in the interstellar medium, planetary

formation and environments conducive to prebiotic chemistry, the

establishment of microbial organisms and subsequent evolution and

potential elaboration of complex multicellular organisms, ecosystems,

societies, intelligence, technological civilizations, and so on. I

studied everything I could get my hands on dealing with the subject. I

began producing paintings and was immediately published. As it

transpired, with all of the commissions I soon acquired, I suddenly

found myself embarked on an early professional career as an astronomical

artist.

I had also begun to train myself in the use of airbrushes to more

easily and effectively accomplish the delicate details and appearance of

clouds with quick-drying water-based acrylic paints. Since the age of 8

I had been an avid sky-watcher, a student of meteorology as well as an

amateur astronomer. I had been fascinated by clouds for as long as I can

remember. (My very earliest memory is of a cumulus-filled sky brightly

back-illuminated by a high sun, over a wide tree-lined park; checking

with my mother, I believe the observation occurred from a baby buggy my

mom was pushing me along in as we strolled along a walk lining a lake

shore park on the North Side of Chicago in the Summer of 1957 when I was

perhaps 16 months old. It is an extremely vivid memory indelibly etched

in my mind...I have even toyed with reconstructing that scene. I might

attempt it one day, but it makes me nervous: it suggests an end to

memory).

In any case, I had amassed a large collection of cloud photographs

for my personal reference years before I had any intention of painting

clouds. In 1974 I discovered the venerable Paasche model AB extra

fine-line airbrush, an airbrush whose unique mechanical design had not

significantly changed since the 1930's and was used for photo-retouching

and by artists working on Walt Disney's early classic animated films

including 'Fantasia'. This unit became my principle tool in the creation

of most of my paintings, and it was the tool I introduced to all of the

members of the team of the Cosmos Artists (as we were known) in order

to facilitate a uniform consistency in the painted artwork for the

visual effects which we were to prepare.

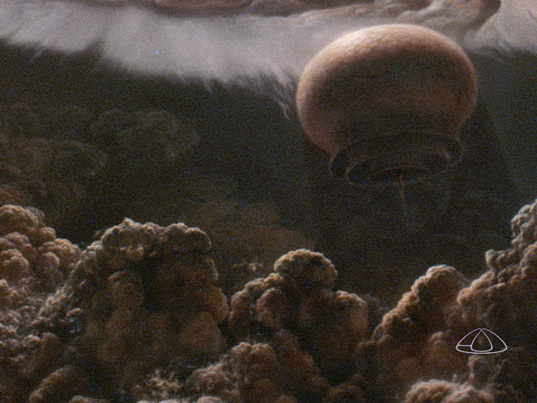

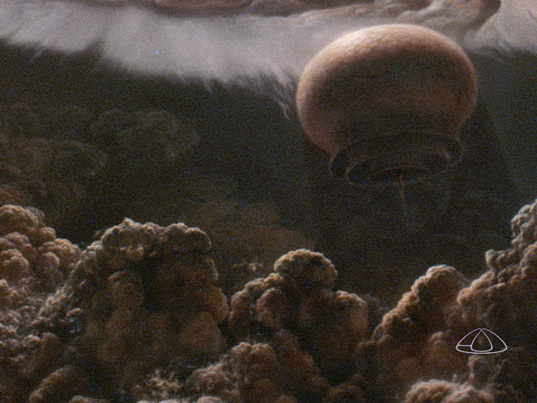

©Adolf Schaller

A "Floater" from Cosmos, Episode 2

Part of the larger mural, "Hunters, Floaters, and Sinkers" painted for the series.

Late that month of September, 1978, I was asked to immediately begin

preparing preliminary concept drawings for what would become HFS while I

was still at home in suburban Chicago. (At the same time I was also

asked to begin painting a sequence consisting of four 15 x 20-inch

panels depicting the final stages of our Sun's life, named by the title I

gave to the first painting in the sequence, "The Last Perfect Day",

which Carl subsequently altered slightly to, "The Last Good Day". That

first painting was the very first of thousands of separate pieces of

artwork I would contribute to the show over the better part of a year -

from conventional paintings and artwork painted on flat acetate sheets

for multiplane animation fx to tabletop models, planetary globes,

asteroids and other models).

By the time I arrived in Los Angeles on February 13, 1979 to join the

team of Cosmos Artists and work on the production of the visual

effects, I had completed many dozens of preliminary concept drawings of

the basic design of the HFS cloudscape environment, along with about a

hundred conceptual designs for a variety of species of the three

principle types which constituted the hypothetical biosphere and its

ecological system: Hunters, Floaters and Sinkers - creatures with

diverse shapes and anatomies, aerodynamic and buoyancy properties,

propulsion mechanisms, feeding modes, social and navigation or migratory

behaviors, communication, reproductive and defense and even stealth

strategies, and more, that would not only fit them for life within a

global atmospheric habitat, depending on conditions at various altitudes

and within clouds of various composition, as well as the other dynamic

aspects of weather, but also provide the basis for local or close-range

interaction with other individuals of the same or different species,

either in encountering those of their own kind (for reproductive

purposes, or to maintain mutual proximity in gregarious social

collections, for example), in encountering potential prey (Floaters

grazed on diminutive but abundant Sinkers, while Hunters ambushed

Sinkers for their stores of purified hydrogen as well as for nutrition),

or encountered potential predators (both Floaters and Hunters could

evolve elaborate defense strategies against attack by other Hunters).

Carl's early speculations on Jovian atmosphere life in the 1960s had

evolved and he eventually worked out the basic hunters, floaters and

sinkers ecosystem which he described in a paper with Ed Salpeter:

"Particles, Environments, and Possible Ecologies in the Jovian

Atmosphere", which appeared in The Astrophysical Journal, Supplement

Series in late 1975. Meanwhile I had been exploring the wide range of

potential planetary habitats and designing a great many life-forms in

the fleshed-out detail necessary for illustration, that could

conceivably evolve and flourish within habitable environments, including

Jovian-type atmospheres.

As I already mentioned, I had the benefit of a decent head start: I

had been studying the range of potential conditions of gas giant

atmospheres, considering those environments as potential habitats

supporting hypothetical biological communities for years before I was

called to work on Cosmos, and I had already composed a number of

cloudscapes that prefigured HFS. In fact, much of the basic cloudscape

is derived from the painting I donated to the Flandrau Planetarium in

the spring of 1978, a work I had started on nearly 2 years before I

commenced work on Cosmos that fall.

I began work on the main Cosmos VFX within several hours of my

arrival. I was whisked from LAX to KCET-TV, which is located at the

juncture of Hollywood and Sunset boulevards, stood around the offices

for a while waiting on another team member, then off we went to the fx

studio the show had contracted to perform the main fx, called Motion

Pictures Incorporated (MPI) located over the Hollywood hills in Burbank

to the north. The Cosmos Artists residence came to be called 'the

Artists Apartment', which was actually a rented 3-bedroom house located

in a relatively quiet residential neighborhood several blocks east and

within walking distance of the KCET offices. We outfitted the house as

an artist's studio, each of us working in their own bedrooms, or

collectively in the living room/dining room on bigger projects like the

large 4-foot diameter Earth globes - a surface globe prepared by Don

Davis on which several of us pitched in on to help, and a separate

'cloud globe' of the same size that was my responsibility. The trip

between the house to MPI in Burbank was our daily commute. That first

night, returning from Burbank, and after that exhausting day that began

early that morning in Chicago, I began work on HFS by preparing the

first of what I thought would total at least three, but not exceed five

30x40-inch panels.

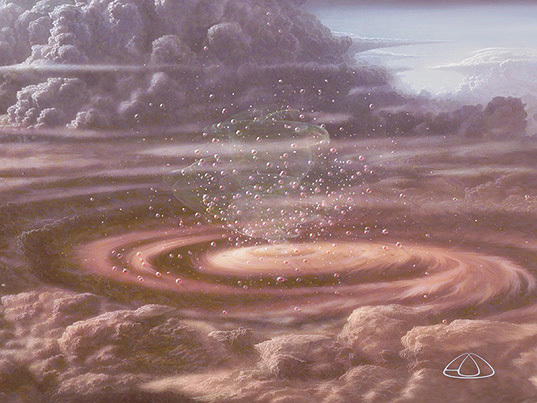

©Adolf Schaller

A Lazy Herd of Floaters

An updated digital restoration by Adolf Schaller of detail in his

original Hunters, Floaters, Sinkers mural which appeared on Cosmos,

Episode 2, which speculates about life in the atmosphere of a gas-giant

planet.

That was to change drastically within the next month. The middle

three panels covered the panorama centered along the horizon. I thought

at first this might be sufficient, but I found that there would be many

opportunities to explore the cloudscape far beneath and high above our

apparent position (which I had calibrated by cloud type and other cues

suggesting that the viewer was located at about the 1 bar level,

assuming ideal smooth and laminar pressure gradient unaffected by

weather). I had arranged for a wide-angle view with a scale of 1 Degree

of arc to the inch.

It was an extremely exciting time for us: one must keep in mind this

was just weeks away from the first of the Voyager flybys of Jupiter that

March, and we all marveled at the awesome images Voyager had been

returning of those incredible cream-in-coffee clouds with

ever-increasing resolution. I was especially keen on studying them to

gain some insights I could transfer into the painting. At the same time,

I was preparing an accurately oblate 18-inch-diameter Jupiter model for

several vfx sequences, and Voyager image prints made available to the

press by JPL were indispensable references. Not every image Voyager

returned was printed, however. I therefore petitioned to spend the night

of closest approach at JPL so that I could study the raw images as they

were displayed on the monitors.

As an aside, I should mention that we had visited JPL on several

previous occasions to see Jim Blinn, who had created astonishing

computer simulations of the Voyager flybys and who would be contributing

a number of those along with other sequences to the show. Jim's

groundbreaking work pioneered the digital fx revolution everyone enjoys

in the motion picture industry today.

The computers he had at his disposal at JPL were costly, huge and

slow by today's standards - it took many days for his setup to render

sequences of a few minutes length. But the results were gorgeous and

mesmerizing. I knew that I was seeing the future in his lab, but I never

dreamed then that it would arrive as soon as it has and with such an

astonishing boost of capacity and speed. Jim insisted he could never

match the complex effects we were performing through traditional

animation methods and camera moves on models and artwork, but it was

certainly obvious to me that none of us could replicate the accuracy of

the motions and trajectory of that little virtual Voyager I saw

pirouetting on his monitors. Jim's sequences had the look of

authenticity which was notoriously difficult to achieve via traditional

vfx methods.

In any case, it was on one of those visits that I noticed there were

half a dozen large monitors set up in an out of the way corner of the

lobby to the von Karman auditorium, where members of the press

congregated, and it occurred to me to be a perfect place to

unobtrusively watch during the spacecraft's flyby. But it turned out

that it was a surprisingly tough sell - nobody thought that an artist

required any such referential input. This puzzling and exasperating

attitude introduced me to a commonly held view amongst scientists and

producers alike that art somehow springs spontaneously out of uninformed

or unstimulated gray matter.

I was increasingly anxious as the flyby approached to have my request

granted, so I asked to meet with Carl privately over at the Artist's

Apartment. I had been enforcing a strict policy of keeping my work on

the HFS panels under quarantine: nobody could see them except Carl and a

few confidants on the team. The reason for this was to avoid

unnecessary disruptions and preserve my concentration against the

well-intentioned suggestions and advice of people. (I liken the

phenomenon to rearranging the furniture physically without being able to

visualize whether a given configuration is optimum: if it was up to

some, a given project would change course so often it would never get

done. The execution of a work is not a time to get distracted by

experiment - that's supposed to be settled with the preliminary

conceptual studies).

To my delight, I got my chance to plead my case: Carl accepted my

invitation to stop by about a week before the flyby, and I displayed the

three central panels arrayed along the horizon, propped up against the

wall side-by-side, to show him how it was progressing. By that time I

had finished most of the areas within 8 to 16 inches of the horizon

centerline and had roughed out the rest of the cloudscape throughout the

remaining area of the panels.

I was very gratified at Carl's reaction to it - he spent several long

silent minutes in front of the panels, slowly shifting from one side to

the other, his eyes scanning the detail along the horizon and the

structures I had established above and below it. When he began to speak

he grew really excited and I fielded his questions the best I could. I

showed him what I had begun to prepare in two additional panels that

could be positioned at the upper left and lower right corners to give

the camera a view of regions close up, far down below and high overhead,

where much of the details of the organisms that I had sketched could be

established. I ventured the possibility of adding two more panels

beneath and above the center panel as well, reiterated that the amount

of work involved in covering so much area on these boards with a uniform

level of detail was very time-consuming and laborious, and that the

schedule may not permit me to get that far to finish those. He stood in

front of the scene and stepped back a few paces as if to take in the

entire scene in his imagination, while pondering silently for another

full minute. Then he said, "Let's fill out the whole thing and make it a

full nine panels."

My initial elation at his reaction to the painting turned to stark

terror. I remember a very unpleasant queasy feeling in the pit of my

stomach as my mind automatically calculated the area involved and I

guess I was at a momentary loss for words. (10,800 square inches - 75

square feet of area to cover with millimeter resolution detail - it was

petrifying). I finally managed to croak out something about how I didn't

have enough time to devote to something that large and keep up my

responsibilities with the rest of the effects. He simply said "Don't

worry, we'll find a way", and just like that the matter was decided.

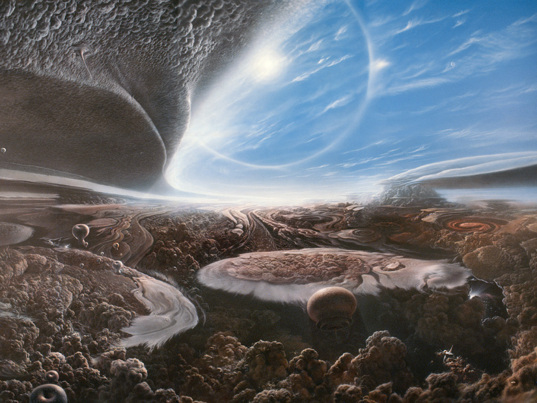

©Adolf Schaller

A Hunter

A speculative hunter animal evolved in the atmosphere of a gas-giant planet. Developed for Cosmos, Episode 2.

I must have been showing my shock, because he cheerfully changed the

subject onto my request to go to JPL for the Voyager flyby. He

reiterated the fact that he didn't want HFS to reflect an explicit

association with Jupiter. I said I understood that perfectly that it was

to be a portrayal of a hypothetical but generic gas giant world. But it

was nevertheless an important opportunity to gain an insight into gas

giant atmospheres. After all, Jupiter is a gas giant planet - and nobody

had ever seen what those clouds really look like at the sub-km

resolution that Voyager would soon return. I considered it vitally

important to the painting, and I said so. It really is that important if

an artist is expected to realize a visualization with maximum realism

and accuracy. (It is generally under-appreciated that the task of

portrayal compels artists to explicitly define the subject - we can't

always enjoy the luxury of ambiguity in dealing with our subjects). I

added that those monitors around the side of the auditorium lobby were

all I wanted to be able to sit in front of so I could sketch and take

notes. He smiled and nodded and said, "Good! I'll arrange it!" And with

that our meeting ended.

So I was there at JPL during the flyby. As full of people as the

auditorium was, that corner was deserted and eerily quiet all that

night. But I didn't pay much attention to that. My eyes and attention

were glued to the monitors and I was soaking in every image that came

up. It was a mesmerizing night; it was as if my mind was transported to

the spacecraft. The memory of it often returns to haunt me in quiet

moments to this day...and, yes, it contributed a great deal - in some

places crucially - to HFS. The main insight that was impressed on me

that night was the prevalence of vortices and eddies, as especially

evident in the turbulent region downstream of the GRS, and in the

interactions between ovals and along the boundaries between bands and

zones, right down to the limit of resolution. In suitably turbulent

regions, vortices and eddies were evident down to the limit of

resolution. That was the single most important insight I derived. It

suggests the preponderance of vortices below mesocyclone scale, and the

vigorous convection evident in many regions is more than sufficient

implication: Jupiter and many other gas giant worlds with deep

convective atmospheres must be full of tornadoes at every scale from the

monstrous down to whirlwinds.

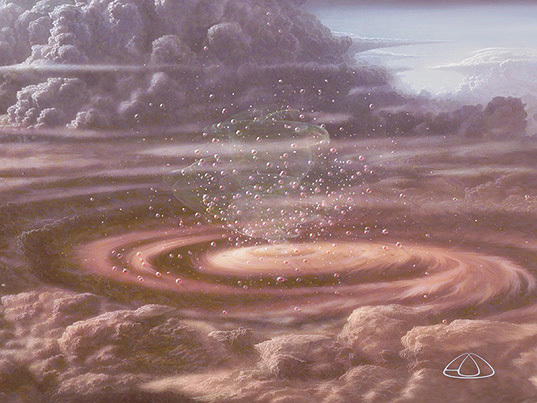

One consequence of the insight on the mural appeared in the form of a

large cyclone reddened by a high population density of "Sinkers" (the

analogue of plankton in earth's oceans) concentrated there to exploit

nutrients updrafted from the depths below. Sinkers are comparatively

tiny, ranging from microbial to large party balloons in size (many of

the larger examples ranging upwards toward weather-balloon-size being

newborn and juvenile Floaters and Hunters), so we only see the reddish

coloration of the vortex from a distance of a few hundred kilometers,

but their presence is also indicated by what they have attracted: a

congregation of "Floaters" lazily grazing on them or giving birth to

them in great numbers over the spot, in a vaguely helical pattern

resembling the molecule of life. Strong convection and turbulence in

Jovian atmospheres is often cited as a detriment to the evolution of

organisms within them, yet such cyclones can conceivably play a

crucially important role in concentrating nutrients and provide stable

refuges.

I also added a more conventionally recognizable 'twister' emerging

out from the ceiling of the canopy at the upper left because I wanted to

give the camera a chance to come across one unobstructed funnel, and

there was no other convenient place to place it. Its bothered me because

strong vertical convection of the sort typically required to form them

would normally not be taking place within a laminar stratus plume of

that kind. It was placed there for the convenience of the shoot: it

wouldn't be very noticeable in the long shots, but only when the camera

panned over the region at close quarters, making the ceiling resemble

the base of a convective cell.

I spent an estimated average of 4 hours of our typical 14-hour day on

it every day over the following 7 or 8 months. Some days it was

difficult to find a half hour for it - on those days I was too exhausted

from pressing duties elsewhere in the fx production. To my dismay that

workload had increased apace with the added challenge of filling out

nine entire panels for HFS. The docket was exhausting.

I don't recall what month HFS was finally ready for the shoot. (I was

far too exhausted by then to notice and, frankly, the Southern

California climate doesn't provide one who grew up in the upper Midwest

and used to annual snowfall enough cues to impress what season it might

be...but I think it had neared the end of 1979 by the time I had

finished HFS for the shoot). I do remember that the final push was a

2-week period staying permanently awake, like a zombie. It's like

sleepwalking, except that though you know (or think you know) you are

awake and your eyes are open, you are in a constant dreaming state. It

was dreadful. I don't remember anything I painted during those closing

weeks except for flashes of the final touch-ups on the stage at KCET.

But I do remember it took me a very long time to recover.

The sequence was shot with director Adrian Malone having Carl

physically walking, speaking and gesturing in front of it. Adrian

meticulously choreographed the camera moves that panned over and zoomed

into sections of the mural to show some of the detail in it with Carl's

narrative voice-over. I was not present at the shoot: I was passed out

in bed in our new apartment in Santa Monica, not remembering how I got

there. I think I was out for almost 3 days. After HFS there were odds

and ends as the work load rapidly eased off. It was the last major

artwork or fx sequence of the production. It was rescheduled that way to

help give me all the time possible (I'm pretty sure, under Carl's

instructions) but it was The Monster among monsters.

Later the next year after Cosmos had aired, I and my fellow vfx

colleagues (belonging to both the Cosmos Artists team and the crew who

worked at Magicam noteworthy for their excellent Alexandrian Library and

the Cosmic Calendar sequences) were awarded the 1980 Prime-Time Emmy

Award for Outstanding Individual Achievement, Creative Technical Crafts.

We assembled up on the stage and accepted the award to a long ovation.

To my consternation my colleagues kept ushering me forward toward the

dais to make the first comments. I was reluctant - I'm not good at

speaking, let alone publicly. All I could manage was to thank my parents

and a special friend for their support. But the one person who inspired

me to explore the possibilities more than any other was Carl Sagan.

Source :

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2013/20131023-on-hunters-floaters-and-sinkers-from-cosmos.html

Ce

genre est à la fois prisée pour ses aventures trépidantes, ses horizons

illimités et ses rencontres inattendues, mais aussi méprisée pour ses

intrigues à peine démarquées des romans noires ou des romans de guerre,

avec souvent le sort de l'univers entre les mains d'un super-héros.

Frank Herbert, l'auteur d'une des plus célèbre saga de space-opéra avec

"Dune" a su déjouer les pièges de la facilité en retenant pour scène

une seule planète sur fond certes d'imperium galactique mais en

inventant des combinaisons inédites à partir d'éléments puisés dans un

grand nombre de cultures. Le space-opéra domine la production littéraire

de SF au cours de l'âge d'or mais commence à régresser dans les années

50. C'est à cette période que le space-opéra va se modifier et passer de

la thématique de l'exploration purement géographique à celle du

développement de l'espèce humaine.

Ce

genre est à la fois prisée pour ses aventures trépidantes, ses horizons

illimités et ses rencontres inattendues, mais aussi méprisée pour ses

intrigues à peine démarquées des romans noires ou des romans de guerre,

avec souvent le sort de l'univers entre les mains d'un super-héros.

Frank Herbert, l'auteur d'une des plus célèbre saga de space-opéra avec

"Dune" a su déjouer les pièges de la facilité en retenant pour scène

une seule planète sur fond certes d'imperium galactique mais en

inventant des combinaisons inédites à partir d'éléments puisés dans un

grand nombre de cultures. Le space-opéra domine la production littéraire

de SF au cours de l'âge d'or mais commence à régresser dans les années

50. C'est à cette période que le space-opéra va se modifier et passer de

la thématique de l'exploration purement géographique à celle du

développement de l'espèce humaine. Ce

genre est à la fois prisée pour ses aventures trépidantes, ses horizons

illimités et ses rencontres inattendues, mais aussi méprisée pour ses

intrigues à peine démarquées des romans noires ou des romans de guerre,

avec souvent le sort de l'univers entre les mains d'un super-héros.

Frank Herbert, l'auteur d'une des plus célèbre saga de space-opéra avec

"Dune" a su déjouer les pièges de la facilité en retenant pour scène

une seule planète sur fond certes d'imperium galactique mais en

inventant des combinaisons inédites à partir d'éléments puisés dans un

grand nombre de cultures. Le space-opéra domine la production littéraire

de SF au cours de l'âge d'or mais commence à régresser dans les années

50. C'est à cette période que le space-opéra va se modifier et passer de

la thématique de l'exploration purement géographique à celle du

développement de l'espèce humaine.

Ce

genre est à la fois prisée pour ses aventures trépidantes, ses horizons

illimités et ses rencontres inattendues, mais aussi méprisée pour ses

intrigues à peine démarquées des romans noires ou des romans de guerre,

avec souvent le sort de l'univers entre les mains d'un super-héros.

Frank Herbert, l'auteur d'une des plus célèbre saga de space-opéra avec

"Dune" a su déjouer les pièges de la facilité en retenant pour scène

une seule planète sur fond certes d'imperium galactique mais en

inventant des combinaisons inédites à partir d'éléments puisés dans un

grand nombre de cultures. Le space-opéra domine la production littéraire

de SF au cours de l'âge d'or mais commence à régresser dans les années

50. C'est à cette période que le space-opéra va se modifier et passer de

la thématique de l'exploration purement géographique à celle du

développement de l'espèce humaine.